Taking it to the Track

In many of the street-driving schools conducted at regular race tracks, the curriculum often includes the opportunity to drive some “hot laps” on the track. Also, in most regions of the country, clubs and organizations sponsor track days where you can get out on the track in your MINI.

At these track-driving opportunities, you’ll be put in the novice group, so you don’t need to worry about having your doors blown off by some hot-shoe in a track racer. But you will have the opportunity not only to work on your basic car control skills, but also to drive a little faster—maybe even over highway speed limits here and there—and work on some advanced driving skills. Here are some tips on the skills you can work on.

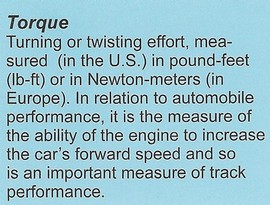

Torque, Power and Gearing

As you watch the races on Speed Channel, or in person at a road-racing track, you’ll notice the wonderful change in the engines’ song as the drivers slow down for corners and then accelerate out. What you’re hearing, of course, is the driver downshifting the car before the corner, and then upshifting as the car gathers speed out of the corner. What’s this all about?

What it’s about is always keeping the car’s engine at its strongest power point when you need pick-up. In an automobile, that relationship is measured not by horsepower, but rather by “torque.”

In technical terms, torque is the twisting power exerted by the engine crankshaft as it rotates. In simple terms, torque is the power to get the car to go faster. It’s that push you feel in the small of your back as you get on the throttle and start to accelerate.

In technical terms, torque is the twisting power exerted by the engine crankshaft as it rotates. In simple terms, torque is the power to get the car to go faster. It’s that push you feel in the small of your back as you get on the throttle and start to accelerate.

Car designers often point out that while owners argue about which car has the most horsepower, the measure that matters more is the torque of the engine, since it is the torque that gets the car to start off from a stop and go faster when needed, such as when passing.

If you’ve ever looked at the plots of engine torque shown in the car tests in the automobile magazines, you’ve noticed that as the engine speed (“rpm” in gearspeak short-hand, which stands for revolutions per minute) rises, the torque increases, but only up to a point. At some point, as the engine speed continues to increase, the torque levels off, and then begins to decline.

For example, in stock condition, the MINI Cooper S produces about 135 pound-feet of torque at 2500 rpm. Torque rises rapidly with engine speed, reaching about 150 pound-feet at 3500 rpm, then more slowly until it peaks at 155 pound-feet at 4500 rpm. At that point, as rpm continues to increase, torque declines gradually to 120 pound feet at 7000 rpm.

What this means in practical terms, is that when driving your MINI, you want to have the engine running between 3500 and 4500 rpm at those times when you need greatest responsiveness and pick-up, such as when passing another car on the highway or pulling away after executing a pass on the track.

If you don’t upshift as you accelerate down the straight, or failed to downshift when entering a tight corner, you’ll find yourself on one side or the other of peak torque just when you need the additional pick-up. That’s why shifting gears is important. For best acceleration, you want to keep the engine revs in the range where the engine is generating the greatest torque.

By the way, downshifting is never used in high-performance driving to slow the car and it shouldn’t be used that way on the street, either; that’s what the brakes are for. (The one exception is in highway driving on long descents down steep hills. There it can be a good idea to downshift to a lower gear and use the engine compression to slow you down. That way you keep the brakes from overheating in case you need them before you get to the bottom of the hill. However, that is a different matter than spirited backroad or track driving.)

Similarly, as the car accelerates, the good driver doesn’t want to push the engine past its physical limits, so as they accelerate they shift up to a higher gear. That way the engine is producing as much power as necessary, but at the lowest possible engine speed.

Shifting Gears

Not surprisingly, there is a right way and a wrong way to shift gears to keep your engine at peak power. Assuming you have a manual transmission, let’s start with your gear shift and the correct way to change gears. While you’re sitting in the car, push in the clutch and then move the gear shift through the gears.

The first thing you’ll notice is that the gearshift seems to be pushing against your hand as you move the lever through the gears. This is because the gearshift is spring-loaded—it has two springs pushing it towards the center “gate” of the gearbox. This is done to make it easier for you to make a clean shift and know where you are, provided you do it properly.

Properly means that you shouldn’t grip the lever as if it were a baseball or bat. Instead, all you need to do is cup your hand around the lever and nudge it in the proper direction. You use the heel and outside of your palm to push it up into first, and use the outside and base of the fingers to pull it down into second while pulling it towards you against the spring.

To move it up into third take advantage of the spring by simply nudging the shift straight up; the spring will push it out of the one-two channel and into the three-four channel. You can use the inside of your fingers to pull it straight down into fourth without exerting any sideways motion.

When you’re ready to shift into fifth, you use the heel of your hand and base of your thumb to nudge the lever up while pushing over against the spring. From fifth to sixth, you use the inside of your first finger to push the lever away from you against the spring, and the crook of your fingers to pull it down.

Incidentally, most of the shifting can be done with a simple finger and wrist motion. If your arm is moving from the elbow or shoulder, you’re using way too much force. And remember, you’re just nudging the lever into place; you shouldn’t be slamming it in. All that’s necessary is that the movement from gear to gear be crisp and definite.

Slamming won’t get the job done any quicker. Your shift needn’t be slow, but excessive speed is just going to cause you to miss shifts. Under nearly all circumstances, you never want to slam the shifter into the next gear. All this does is cause unnecessary wear on the springs and gears without appreciably speeding up the gear change.

Here’s another tip about that gear shift. Casually resting your hand on the gearshift while driving or sitting at the stop light is also a no-no. It may look cool, but that constant pressure will wear against the springs and gears and eventually cause gearbox problems. Unless you are actually making a shift, your hand belongs on the steering wheel, anyhow.

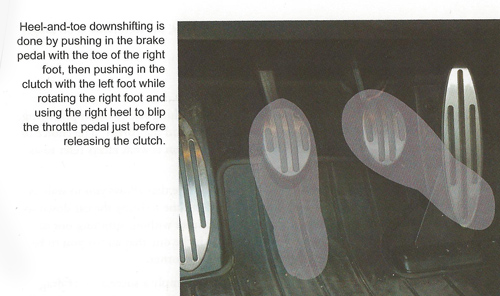

Heel and Toe Downshifting

In normal driving, very few people downshift, since the MINI engine can pull pretty strongly from very low rpm and there are few times when the additional torque is really necessary. But if you want to practice for the day you start doing hot laps at the race track, you can start working on how to downshift, using the technique called “heel-and-toe” shifting to make those shifts as smooth as possible.

Essentially, what you are going to do is make it easier for the engine to cope with the changes in gears by giving the throttle a little blip while you’re downshifting. That way, before the shift is completed, the engine is already spinning close to the higher rpm required in the lower gear. Done properly, this little blip of the throttle will make your driving much smoother, and eventually much faster.

What makes this process a little complicated is that you are going to start downshifting at the same time that you are braking to get ready for the corner. At the same time that you’re putting on the brake with your right foot, you’re going to want to tap the gas pedal with your right foot. “But wait a minute,” you say. “I only have one right foot.”

Right you are. So what you will do is to push the brake in with the toe of your right foot, and by twisting your foot slightly, give the throttle a nudge with your right heel. If it’s more comfortable for you, you can push the brake with your heel and the throttle with your toe. That’s why the technique is called heel-and-toe. (Though to be honest, some people use one side of the foot on the brake and the other side of the foot on the gas. Whatever works for you.)

So here’s the sequence: As you get ready to turn a corner that is going to require that you exit in a lower gear than you entered, you will start to brake with your right foot and at the same time push in the clutch with your left. With the clutch in, you’ll slide the gear shift into the next lower gear and about the same time blip the throttle. With the engine still revving up from the throttle blip, you’ll let out the clutch. Brake, push clutch, shift/blip, release clutch.

Right now this may seem a little like patting your head while rubbing your stomach, but a little practice will make it all work. Incidentally, if anyone asks, you are not “double-clutching.” Double-clutching is actually a more complicated process that requires releasing the clutch slightly at the point that the throttle is blipped in order to get the gears spinning faster, then pushing it back in to shift the gear, before releasing the clutch. Thankfully, with modern engines and gear boxes, the technique is no longer required, except on some really, really old vintage cars.

Of course, if you remember the original cornering sequence we just discussed, we didn’t discuss shifting gears. That does add one additional step to the sequence. However, the downshifting should be completed during the early part of the braking process, while the car is still going in a straight line. By the time you start to make the turn, you want all your shifting done, so you can have both hands on the wheel through the corner.

The Cornering Line

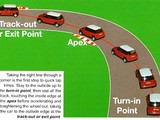

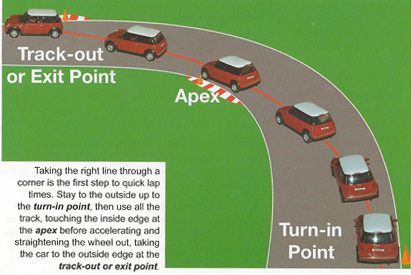

In preparation for your first driving class, and as something else to begin practicing, let’s talk about the safest and most efficient way to get around the corner. The choice of turn-in, apex, and exit points, and the pathway between them is what racers refer to as the “line” around the corner.

The optimal line around an individual corner is the one that allows you to wait as long as possible before braking, while still having enough time to bring the car down to a speed that will allow you to take the car around the corner without spinning out or sliding off the track. More important, the optimal line is the one that allows you to be going as rapidly as possible at the point when you exit the corner.

It’s an old saying around race tracks that all racing is simply a succession of drag races from corner to corner. Picking the correct line around the corner is not necessarily a matter of getting around each corner as fast as possible. Instead, it is a matter of setting the car up so that you can win the drag race to the next corner.

Where you exit, and how fast you exit, depends entirely on where you start to make the turn. Selecting the turn-in point is critical to getting the corner right. After that, everything else is just follow-through.

We can start by thinking about the most basic corner, a 90-degree turn. This is a good place to start since most of our everyday driving is going to involve making right-angle turns on city streets, so there will be lots of opportunities to practice the technique.

And remember, you don’t have to be going fast in order to practice and get the moves down. In fact, for the first 100 or so times you turn the corner, you’ll have trouble remembering everything in the right order, even at normal street speeds. But practice the technique and when you do get on the track, you’ll be amazed at how soon you’ll feel comfortable on higher-speed corners, while your less-practiced friends are still looking confused as they lurch around the corner.

The first step in taking a corner is to move as wide as possible to the “outside” of the corner (the side opposite to the direction you’re turning). On the street or highway, this will usually be the center line or curb. (Of course, on deserted roads with no obstructions, where you can see all the way around the corner and up the road a good distance you might be able to go wider.) Once you’re on the track, you’ll be moving clear to the edge of the track before beginning your turn.

You’ll drive at the edge, while completing your heavy braking (and your downshifting, if the corner requires it), until you can see around the corner. While this isn’t necessarily the smoothest arc around the corner, it will be the most efficient line around the corner in terms of exit speed. It is also the safest, since you will be able to see any obstructions in your path.

At that point, you’ll begin to turn in (which, as we noted above, is called the turn-in point) and start to release your brakes. You will want to aim for the inside edge of the corner—remember, earlier we called that the “apex” of the corner—while looking for the point where you will be completing your turn and will once again be at the outside edge of your lane, or the road, the “exit point” or “track-out point.” Remember that you’re looking at where you want the car to go, not just where it is aimed at the moment.

As you reach the apex of the corner you should be off the brakes completely and already starting to ease onto the throttle. As soon as you begin straightening the wheel, you’ll roll onto the throttle and start to accelerate.

You can see from the diagram that the arc of your curve is tightest just past the turn-in point, and widest as you come out of the turn. This will allow you to get on the throttle as hard as conditions permit as early as possible and start that drag race to the next turn-in point.

The optimal line through a single corner is going to start and end at the far outside limits of the available track or lane. As you progress in racing, you’ll often be reminded to “use all the track.” What the instructor means is that if you didn’t start and end the curve at the far outside, while nearly touching the inside limit—curb, berm, or edge of the pavement—at the apex point, you will have made too tight a turn and sacrificed some of that precious speed you need.

Also notice that on this line, the apex—the point at which you touch the inside limit—is just a little way around the corner, rather than being at the actual geometric point of the corner. That “late apex” is usually the best line, since you have a good sight-line down the road when you start your turn, and that same long straight line along which to accelerate as you complete the turn.

You might think about what happens if you get a little tense and try to “hurry” the corner. You’ll start to turn in sooner than the person who’s following the line we’ve just described, but at best you won’t be able to get on the throttle until later in the turn than the other driver. At worst, you will find yourself, as racers say, “running out of road” before you’ve completed your turn, and risk running off the track.

Now all of that is a lot to practice all at once, which is why we recommend that you start now, rather than waiting until you get into the driving course. Incidentally, during the driving course, the instructor will most likely mark off the course with pylons or markers to show you the turn-in point, the apex, and the exit, which will make it a little easier. But daily driving is like rally driving; no one has put pylons out to show you the correct line, so get used to finding it on every corner on your own.

The entrance and exit ramps on limited-access highways make especially good practice areas, since you aren’t likely to encounter anyone going the other way, and the range of speed is as wide as you’ll encounter on most corners of most race tracks.

The best place to practice is on a corner you take every day. That way you can start at a fairly slow speed, and gradually speed up as you get used to the corner, changing the point where you start and end your braking, turn in for the corner, apex it, and come out at the exit point.

If you find that you are having difficulty getting around the corner, it means either that you’re going in too fast, or you’re turning too early. If that’s the case, trying slowing down a little, which will allow you to turn more tightly at the beginning, and turn in later, which will give you more room to finish the corner at the end.

As racing drivers learn new tracks, this is exactly what they are doing; searching for the optimal points and speeds to start and end each phase of each corner, then memorizing those points so they can repeat them lap after lap during an actual race.

When taking the corners, keep thinking about weight transfer as you brake, turn, and accelerate, feeling the car’s weight shift from back to front and corner to corner through the process. Downhill skiers and horseback riders often find that this process is very familiar, it’s just that there is a lot more of you to think about as the car increases and extends your mass.

As you round every corner on your way to work or wherever, make your braking, turning, and accelerating as smooth as possible and try to pick a good line around each one of those corners. If you do your practice diligently every chance you get, pretty soon you’ll start to feel at one with the car, anticipating the weight transfers and feeling yourself going with them, with no abrupt transitions and with as much speed as the situation allows. In short, you’ll really be motoring.

Motoring On

Consider the upgrades we’ve suggested as means to improve the performance of your MINI, but whether or not you decide to make changes in the car right now, don’t wait to start working on your driving. Use a good driving position, practice smoothness in your starts, stops and turns, and try to find a good line around every corner. And take the next possible opportunity to take an advanced driving course so you can learn and practice the skills that will allow you to drive your MINI in the way it was intended.

After your driving school experience and with a few miles under your tires, you may find that you want to get even more out of your MINI. In the next section, we’ll discuss additional improvements that will prove their worth on the roadtrack or autocross course, and we’ll present some more advanced driving skills you’ll want to master to take advantage of those improvements.

Go to What Can We Do Next?